By Josh Gray and Maria Monahan

Introduction

Hospitalized cancer patients face difficult decisions in balancing quality and quantity of life. For patients receiving care in community or rural hospitals, one such decision is whether to transfer to more specialized cancer programs. Transferring might extend survival, but receiving care far from home could mean a lower quality of life in a patient’s last weeks, due to the difficulty of the transfer itself, the experience of being away from home, and the side effects of treatment. Some high risk patients who are transferred face poor prospects, raising the question of whether palliative care might be a better option for them.

Analysis

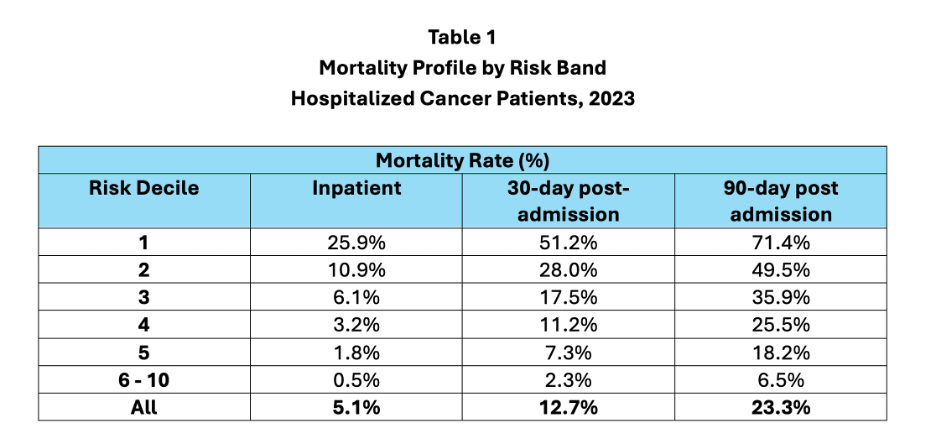

We analyzed all Medicare fee-for-service inpatients hospitalized with cancer DRGs who were transferred from one hospital to another. In 2023, 2.2 million Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries were hospitalized with a cancer DRG. Of those, 264,551, or 11.9%, were transferred to another acute care facility, including PPS-exempt cancer hospitals and other tertiary facilities. Table 1 shows inpatient, 30- and 90-day post admission mortality rates for patients by decile of predicted mortality risk calculated on the date of transfer.[1]

For the subset of transferred patients, 5.1% died in the hospital, 12.7% died within 30 days of transfer, and 23.3% died within 90 days of transfer. However, mortality varied dramatically by risk level. Transferred patients in the highest risk decile had poor prospects: 25.9% died in the hospital they were transferred to, 51.2% died within 30 days, and 71.4% within 90 days. The second risk decile had a 90-day mortality rate of 49.5%. In contrast, among the 50% of transferred patients at lowest risk, only 0.5% died in the hospital, 2.3% died within 30-days post-transfer, and 6.5% died within 90-days post-transfer.

The Importance of Shared Decision Making

The risk profile of transferred patients raises important issues. In some cases, the transfer of individuals at extremely high-risk is entirely appropriate: a patient may be willing to be transferred and to receive aggressive treatment if that will result in an increased chance at longer survival, even if those chances are slim.

However, we speculate that some transferred patients in the top risk deciles would elect not to transfer if they fully understood their survival prospects. More concretely, of the approximately 26,000 Medicare fee-for-service patients in the top risk decile at point of transfer, how many accurately understood their chances of survival in three months (and would have made the same choice if they had)? What is important is that the decision is shared between provider and patient and that providers clearly communicate the patient’s chances of survival given transfer and aggressive treatment. Providers should also ensure that a strong palliative option is available for those who opt for comfort.

Fortunately, given the greater accessibility of data and improvements in AI, this type of information is increasingly accessible to patients and their families. For the last five years, Health Data Analytics Institute has been developing HealthVision, a software platform that provides continuously updated patient risk profiles. Using HealthVision, providers and patients can have honest and realistic conversations about the tradeoff between quality and quantity of life. The goal is to use specialized resources that are in line with what patients and their families need and want.

If you work with a hospital and are interested in understanding the survival patterns of patients transferred to or from your facility, please reach out – we would be happy to provide you with this information.

Josh Gray, VP of Analytic Services, HDAI ([email protected])

Maria Monahan, Data Analyst, HDAI ([email protected])

SHARE